Tyranny of the Minority (Part 1)

A shrinking, fiercely ideological party is clinging to power no matter the cost. Buckle up.

In their 2012 book It’s Even Worse Than It Looks, published before anyone imagined a Trump presidency, the political scientists Norman Ornstein and Thomas E. Mann incisively identified the root of Washington’s dysfunction. Radicalized by talk radio and amplified by social media, congressional Republicans had begun behaving like a parliamentary party: “ideologically polarized, internally unified, vehemently oppositional, and politically strategic,” they wrote. In a constitutional system with separation of powers, that “makes it extremely difficult for majorities to work their will.”

In parliamentary systems, majority parties can effect their agenda almost unchecked. On the other hand, constitutional systems operate on norms, good faith, and compromise, which affords opposition parties enormous leverage to obstruct the majority. Once Republicans began employing maximalist tactics against the Obama administration—and found them effective in achieving their political goals—the democratic machine started to break down.

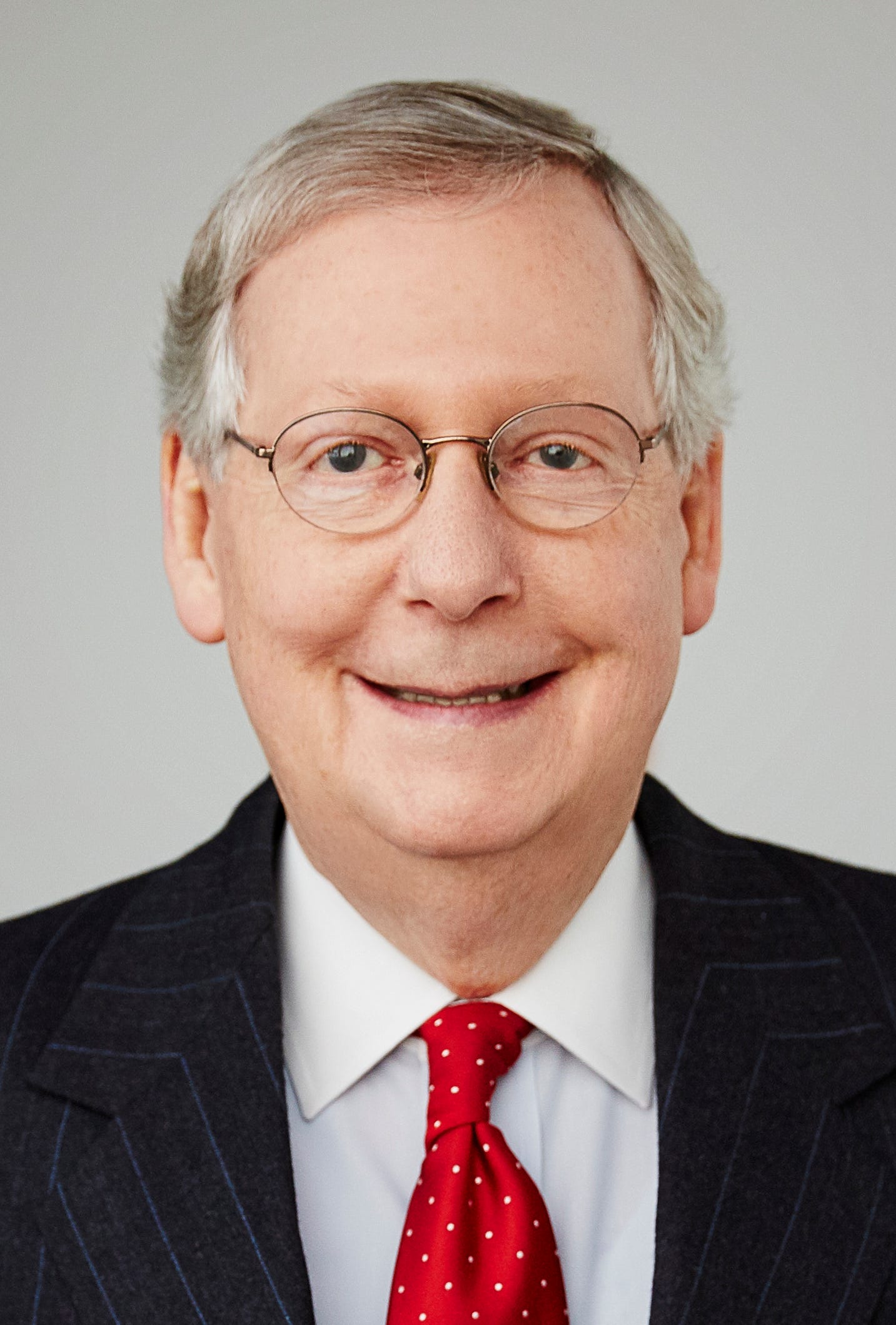

Ornstein and Mann were animated by the unprecedented hostage-taking of the 2011 debt-ceiling crisis, in which House Republicans threatened to default on the country’s credit if President Obama and the Democratic Senate didn’t accede to their demands for draconian discretionary spending cuts. This was accompanied by an unprecedented use of the filibuster to block Obama’s policies. Later came Mitch McConnell’s unprecedented blockade of judicial nominees during Obama’s last two years, after Republicans won a Senate majority in 2014, including his unprecedented refusal to even allow hearings, much less a vote, on Merrick Garland’s nomination to the Supreme Court.

It wasn’t just the Supreme Court, either. In 2015–16, the Senate confirmed just two federal appellate judges and 18 district court judges. (For comparison, in George W. Bush’s final two years, the Democratic Senate approved 10 appellate judges and 58 district judges.) As a result, Donald Trump took office with more than 100 judicial vacancies. McConnell then changed the rules to approve Trump’s nominees more quickly, allowing the president to reshape the federal district and appellate courts for a generation—other than the 210,000 dead bodies, perhaps his only lasting achievement.

Of course, Trump is also reshaping the Supreme Court: Justice Neil Gorsuch, appointed to fill the seat that should have been Garland’s; Justice Brett Kavanaugh, confirmed in 2018 despite allegations of sexual misconduct; now, Amy Coney Barrett, selected to fill the seat of Ruth Bader Ginsburg a month before an election the president and Senate Republicans seem likely to lose.

If Barrett is confirmed, three of the Court’s nine members will have been appointed by a president who earned 3 million fewer votes than his opponent and confirmed by a Senate majority that represents 15 million fewer Americans than the “minority.” They will join two other justices appointed by a Republican president who lost the popular vote to form a far-right majority that can overturn the Affordable Care Act, roll back abortion and LGBTQ rights, gut environmental and labor protections, enable conservative state legislatures to through up barriers to the ballot, and block legislatively enacted progressive reforms for decades to come.

Since 1992, Republicans have won the presidential popular vote just once, yet, on account of the Electoral College, they’ve held the White House for 12 of 28 years. In the U.S. Senate, the fact that Wyoming gets the same number of seats as California, a state with 70 times its population, redounds to conservatives’ benefit. In recent U.S. House elections, Republicans have won more seats than their share of the national vote.

The disparities created by these counter-majoritarian institutions have convinced the national media—and much of the navel-gazing Democratic Party—that the country is center-right. By any objective metric, it is not. But since that reality isn’t reflected in swing states or the composition of Congress, our perceptions of the country’s ideology get warped in a way that benefits white conservatives.

There’s something else at work, a sentiment Ornstein and Mann pointed out nearly a decade ago that has only intensified since. As the GOP became more and more like what one former Republican congressional staffer described as an “apocalyptic cult”—ignoring scientists, engaging in conspiracy theories, catering to extremists—it also grew “dismissive of the legitimacy of its political opposition,” Ornstein and Mann wrote.

In other words, even if Democrats won more votes, they aren’t entitled to govern. Their voters don’t reflect the “real” America. Their policies infringe on liberty and must be resisted. In Manichean politics, popular sovereignty should be defied when the masses are wrong.

This sort of delegitimization emboldens the fringes, as we saw in Michigan last week, when the FBI arrested right-wing militia types for plotting a coup against the governor over her “treasonous” COVID-19 response. No less important, when you deem your opponents inherently illegitimate, you have no obligation to compromise. When politics becomes a zero-sum game, you use power as a means to its own end.

Witness the tenacity with which Republican legislatures in North Carolina, Wisconsin, and other states sought to suppress Black votes through aggressive gerrymandering, voter ID laws, and other initiatives over the last decade. Witness, too, the Trump campaign’s all-out war against voting by mail this year.

This is how the tyranny of the minority works.

It’s important to acknowledge here that, at least for now, this radicalization goes one way: The country is asymmetrically polarized. Republicans are far-right insurgents, so much so that they were incapable of governing even with unified control. Democrats, while they’ve become more liberal (as has the country), are still a center-left party.

Yet as the GOP has lurched rightward, it has become entirely dependent on a shrinking demographic of older white conservatives, usually men, usually without college degrees, usually evangelicals. But the more that cohort shrinks, the more tightly the party clings to power through any means necessary—finding increasingly strained rationales to justify itself.

So it is with the rushed nomination of Amy Coney Barrett, for whom the McConnell Rule of 2016 does not apply.

And so it was that, about 30 minutes into last week’s vice presidential debate, Utah Senator Mike Lee—a likely candidate for president in 2024—tweeted: “We are not a democracy.”

More on that in part 2.